Fate often has a way of intervening and fundamentally altering your life in ways you never saw coming. Such was the case with a Texan named Johnny Stout.

Stout had no idea that his life was about to change profoundly when he happened to walk into the knifemaking shop of J.B. Moore in Fort Stockton, Texas, in 1983. Stout, then a 40-year-old employee of Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, was completely unaware there was such a thing as a handmade custom knife.

“I was just fascinated,” he said. “To actually make one was so foreign to me, I was just taken in immediately and I knew this was something I wanted to do.”

Many of Stout’s high-end knives feature Damascus blades, ornate engraving, gold inlays and materials such as mother of pearl for the scales. This Vaquero model is a double-action automatic.

He said he must have asked Moore a thousand questions, and Moore graciously agreed to teach him how to make knives. Stout left Moore’s shop with a used bandsaw and a square wheel grinder. Living in Odessa, Texas, at the time, Stout spent many weekends visiting and learning from Moore while putting together his own shop at home. In time, he acquired enough of the basic skills in grinding, buffing, and polishing to build basic fixed-blade knives of his own, often with a distinctive Texas flair.

JOHNNY STOUT KNIVES KNOWN FOR EXCEPTIONAL FIT AND FINISH

“Once I got a few knives out there—there were just not many people making knives then—I would set up at gun shows and sell knives,” he said.

The first three custom knifemakers Stout met when he was getting started were J.B. Moore, Weldon Whitley, and Loyd McConnell, and they continue to influence his work today.

“From these three, I learned that fit and finish are number one, and should always be number one on any knife that I build,” he said.

His philosophy on knifemaking is straightforward: Always do the very best job you can do, and never stop learning.

“Don’t accept your last knife as the best one that you’ll ever build,” he said.

“Don’t accept your last knife as the best one that you’ll ever build”—Johnny Stout

That philosophy has served him well. Over time, Stout’s reputation and customer base grew, and when Stout retired from the phone company in the mid-1990s, he started making knives full time. Today, at age 78, Stout hasn’t slowed down. He’s still turning out everything from basic hunting knives to museum-quality pieces that often fetch high prices from his shop in New Braunfels, Texas.

“If I’m out of the shop for a couple of days, I start going stir crazy,” he said. “I still love it today. The ‘new’ hasn’t worn off. I don’t think it ever will.”

STOUT ADIMIRED BY HUNTERS, COLLECTORS ALIKE

Over the years, Stout’s work has evolved with an emphasis on providing the collector market with highly embellished knives using materials like Damascus steel, mother of pearl, and mammoth ivory. He has sold several knife models for as much as $10,000, and one knife he donated for a fundraiser sold at auction for $35,000.

Stout said he also has a good following of customers for his hunting knives. A basic field-grade knife, with high-grade steel, wooden or Micarta handles, and no bolster, sells for about $350, with the price rising as options are added. His most popular hunting knife is a model called the Rio Grande Skinner.

He also makes a two-knife set, provided in a custom two-knife sheath with a Lone Star medallion, called the Texas Trophy Set. One knife blade has a full belly for skinning, while the other has a slender blade for doing more detailed work.

From the simple to elegant and ornate, Johnny Stout’s knives vary widely in price according to the materials and amount of work that go into them.

Knives made for collectors are, of course, far more intricate and embellished, often with feather-pattern Damascus blades and ornate handles made of exotic materials with intricate engraving, gold inlays, and other refinements. A good example is a knife based off a model created by the late Warren Osborne, who Stout describes as one of the best knifemakers ever. Stout asked Osborne’s widow if he could use one knife pattern that Stout really liked, and she consented.

“If I’m out of the shop for a couple of days, I start going stir crazy. I still love it today. The ‘new’ hasn’t worn off. I don’t think it ever will.” – Johnny Stout

One of Stout’s more distinctive offerings for hunters is the Texas Trophy Set, a matching set consisting of a skinner and a finer blade for more detailed work.

“I wanted to enlarge it and make an automatic out of it,” he said. “It was really a tribute to Warren.”

The result is a knife he calls the Legacy. The Legacy will only be a limited offering. Stout plans to make just 10 of them, and he’s produced three to date.

COWBOY MODELS

Other examples include several models with names Stout said are loosely based on an idea he had when thinking about Mexican cowboys, resulting in model names such as Vaquero, Amigo, and Compadre. One version of the double-action auto Vaquero model featured a 3 ¾-inch Doug Ponzio Turkish Twist Damascus blade, fluted mammoth ivory scales with 14k gold wire inlays, and hand-engraved bolsters and backspacer by master engraver Wes Griffin.

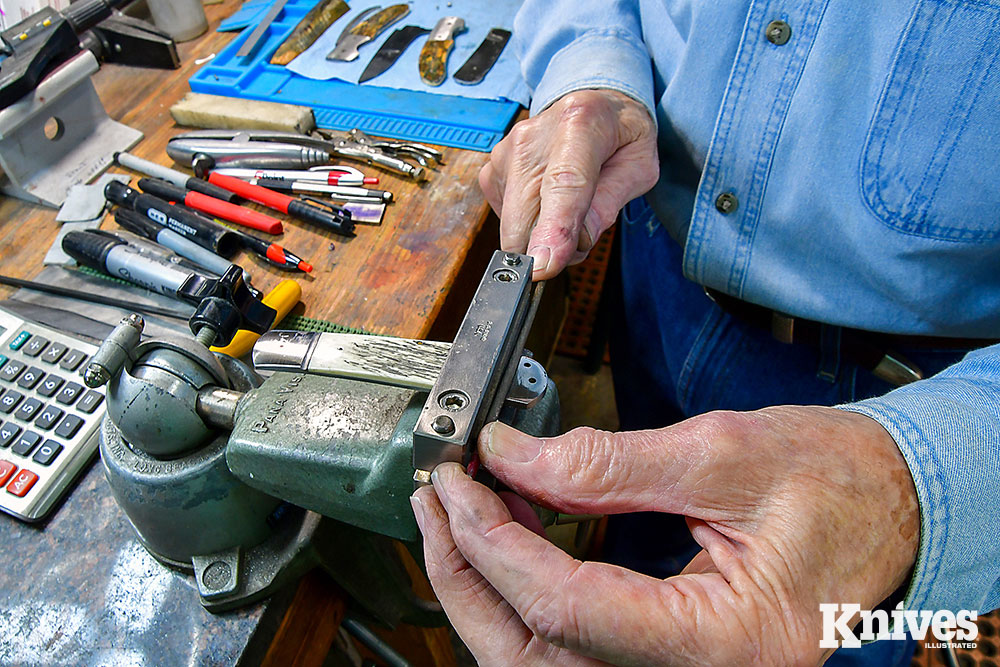

Stout, who grinds all his own blades, has his students use softer-steel “practice” blades before tackling the real job. Here, he demonstrates use of belt grinder on a practice blade.

A typical Compadre is a fine folder that uses the same-pattern 3 ¾-inch Damascus blade and has mother of pearl scales and matching stainless Damascus bolsters engraved by Joe Mason. A typical Amigo model, which is also a fine folder, is fitted with a 3-inch composite ladder-pattern Damascus blade, mother of pearl scales, and stainless bolsters engraved by Wes Griffin.

“I’m very fortunate that several collectors have been very gracious and continue to commission my work, and constantly are challenging me to raise the bar higher,” said Stout.

At age 78, Johnny Stout still looks forward to getting up every morning and working in his shop. “If I’m out of the shop for a couple of days,” he said, “I start going stir crazy.”

HIS PERSONAL FAVORITES?

That’s not to say he doesn’t have his favorite knives to make. For fixed-blade knives, he prefers to make skinners and hunters, both with 3 3/4-inch blades. He uses a variety of materials but likes to stick with CPM (Crucible Particle Metallurgy) blades. CPM is a method of producing higher-alloyed grades of superior quality steel that offer improved machinability. For folders, there’s actually very little limit to the types of knives Stout makes.

“I don’t really make just one model,” he said. “I build everything from slipjoints, lockbacks, and automatics to flipper designs.”

Of course, the difference in prices his knives command depends on the materials selected and the degree of work that goes into each knife.

Stout is currently producing a limited run of 10 knives he calls the Legacy. The knives were conceived as a tribute to the late knifemaker Warren Osborne.

“A fixed-blade has possibly five parts—a blade, two bolsters and two handle scales,” he said. “Many of my folders will have 25 to 30 parts, depending on the mechanism. An automatic will have a blade, two bolsters, two handle scales, a backspacer, a kick spring, a pivot, two bearings, 15 screws, a push button, a push button cabochon, a push button spring, a thumb stud, and a thumb stud cabochon.”

Johnny Stout reaches into what he calls the “wood drawer” in his shop. That’s where he stores materials, from the mundane to the exotic, that become scales on his knives.

A peek at Stout’s website (StoutKnives.com) reveals page after page of photographs of a wide variety of knives ranging from elegantly simple models to some absolute works of art produced by a master knifemaker at the top of his game.

These include models with names such as the Baron, the Aristocrat, the Squire, the Monarch, the Patron, the Zodiac, and the Osprey. Less ornate but highly functional everyday models include the pocket-clip Barracuda, the Trapper, the Vanguard II, and the Tactical Gemini.

A VERY LUCKY MAN

For someone who can turn knives into art, Stout’s personal taste in everyday knives is surprisingly simple.

“Believe it or not, my most useful daily carry knife is a Swiss Army Knife,” he said. “I also carry a three-blade stockman.”

While some things have changed during Stout’s lifetime in custom knifemaking, one thing hasn’t.

“It’s hard to believe, in today’s world, but many people still don’t realize that we are here, and that we make knives.”

In addition to making knives, Stout enjoys teaching the art to others. He generally teaches one or two classes per month at his shop, limiting attendance to only two students at a time. Here, Dillon Boyd, one of his students, works at completing a folder under Stout’s tutelage.

Several TV shows have helped expose custom knifemaking to the public, he said, and he credits the American Bladesmith Society with taking the lead in teaching, training, and constantly exposing custom knifemakers to the global public. Additionally, he said, the “tactical” market is constantly introducing more and more people to handmade knives, and factory knifemakers are building many of their models based on custom knifemakers’ patterns or models.

Over the years, Stout’s work has been recognized with numerous awards. In 2021, he won an award for the best folder at the Arkansas Knife Show and was invited as a guest knifemaker at the semi-annual Art Knife Invitational in Las Vegas, which showcases the work of small number of the world’s most collectible knifemakers before an invited group of distinguished collectors.

Stout said he feels blessed that he can still get up and work every day at his age, and he attributes much of his success to the support he gets at home.

“My wife is an even bigger knife nut than I am,” he said. “She collects knives and goes to the shows with me. With that sort of support behind you, it helps and makes things so much easier. I’m a very lucky man.”

TEACHING THE NEXT GENERATION OF KNIFEMAKERS

Just as Johnny Stout received the benefit of mentorship from J.B. Moore and others in learning his trade, he has continued that tradition by teaching aspiring new knifemakers for the last decade or so. He teaches only one or two classes a month at his shop, and he limits the number of students to two per class so he can provide students with plenty of personal attention. Classes are offered in basic knifemaking, and in making fine folders and flipper folders. Stout also offers a couple of “Your Choice” classes each year.

“About the only thing I don’t teach is how to make automatics,” he said. “It’s just too complex. It takes me about two weeks to make one myself.”

His advice to aspiring knifemakers is straightforward and to the point.

“Invest in quality tools and equipment, get good training and build a quality product,” he said. “Honor your work.”

SOURCE

Stout Knives

StoutKnives.com

830-606-4067

Johnny@StoutKnives.com

Subscribe / Back Issues

Subscribe / Back Issues